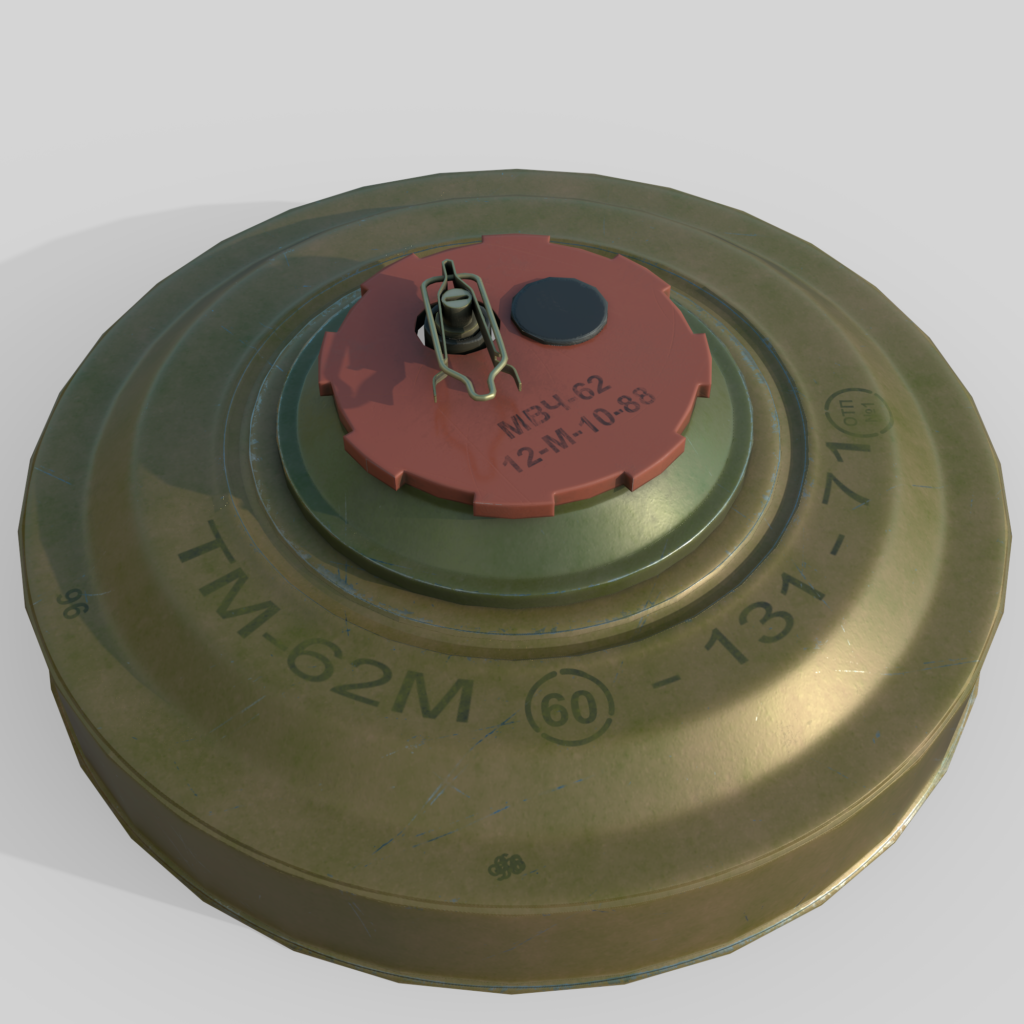

TM-62M

The TM-62M is a Soviet-designed anti-tank blast mine developed in the early 1960s as part of the TM-62 mine family and remains in widespread use today. The “M” designation refers specifically to the metal-bodied variant, which distinguishes it from plastic, rubber, or composite versions of the same series. The mine has a cylindrical steel casing with a flat pressure plate on the top surface and is typically painted olive green or dark brown. When emplaced in soil, roads, or rubble, it can visually resemble a metal lid, industrial scrap, or buried infrastructure, making it difficult for civilians to recognize as an explosive hazard.

The TM-62M is filled with a high-explosive main charge weighing approximately 7.0 to 7.5 kilograms, depending on the production batch and filling method. The most common explosive used is TNT (trinitrotoluene), but the mine is also known to be filled with TNT-based mixed explosives such as TG-40, TG-50, or MS, which combine TNT with RDX or other energetic components to increase brisance and reliability. These explosives are cast or pressed into the metal casing, forming a stable but highly destructive charge designed to rupture armored hulls, break tracks, or destroy vehicle underbodies.

Detonation is initiated via a replaceable fuze system, one of the defining features of the TM-62 series. The mine itself does not contain an integral fuze; instead, it accepts a wide range of Soviet and Russian mechanical and electronic fuzes, allowing it to be adapted for different tactical purposes. The most commonly used fuze is the MVCh-62 pressure fuze, which activates when a heavy load—typically between 150 and 500 kilograms—is applied. This ensures detonation under tanks, armored vehicles, trucks, and civilian cars, while generally preventing activation by a single person on foot.

In addition to pressure fuzes, the TM-62M can be fitted with magnetic-influence fuzes, such as the MVE-72, which respond to changes in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by large metal masses passing overhead. These fuzes allow the mine to detonate without direct contact, increasing lethality against armored vehicles equipped with mine rollers or plows. The mine can also accept tilt-rod fuzes, such as the MVS-62, which detonate when a protruding rod is pushed or tilted by a vehicle, extending the trigger height above ground level.

Crucially, the TM-62M can be configured with anti-handling or anti-lift devices, either integrated into the fuze or added as secondary components. In these configurations, any attempt to move, rotate, lift, or disarm the mine can trigger detonation. Unlike some modern mines, the TM-62M does not have a self-destruct or self-neutralization mechanism, meaning it remains active indefinitely. Over time, corrosion of the metal casing, degradation of the fuze, and environmental stress can make old mines more sensitive and unpredictable, significantly increasing the danger during clearance operations.

Detection of TM-62M mines relies primarily on metal detection, as the steel body produces a strong signal. However, this advantage is often offset by deliberate concealment. Mines are frequently buried deep in roadbeds, hidden under asphalt, placed beneath concrete slabs, or embedded in debris. In combat zones and liberated areas, the presence of scrap metal, shell fragments, and destroyed vehicles creates false signals, slowing demining efforts and increasing risk. Visual detection alone is unreliable, especially in vegetation, snow, or damaged urban terrain.

Although designed as an anti-vehicle weapon, the humanitarian impact of the TM-62M is severe. Civilian vehicles, buses, agricultural machinery, emergency services, and humanitarian convoys are all vulnerable. Detonations often result in multiple fatalities, traumatic amputations, severe burns, and complete vehicle destruction. Roads, bridges, and supply routes become unusable, while farmland is rendered unsafe, directly affecting food security and economic recovery.

Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, TM-62M mines have been used extensively by Russian forces in defensive minefields, retreat routes, road denial operations, and large-scale area contamination. They have been found in frontline regions and in territories later liberated by Ukrainian forces, including villages, forest belts, highways, and agricultural fields. Many minefields were laid without proper marking or documentation, leaving civilians exposed long after active fighting moved elsewhere. As people return to their homes, vehicles continue to trigger these mines, causing ongoing casualties and reinforcing long-term displacement and fear.

From a legal perspective, anti-tank mines such as the TM-62M are not prohibited by the Ottawa Convention, which applies specifically to anti-personnel mines. Their use is instead governed by international humanitarian law, which requires distinction, proportionality, and precautions to protect civilians. In practice, widespread and unrecorded deployment has demonstrated how even legally permitted weapons can produce indiscriminate and long-lasting civilian harm.

The TM-62M stands as a classic example of a Cold War weapon whose military utility is overshadowed by its post-conflict consequences. Powerful, adaptable, and simple to deploy, it remains effective against armored forces. At the same time, its durability, lack of self-neutralization, and frequent use in civilian environments make it a persistent threat for decades. In Ukraine, the continued presence of TM-62M mines highlights how anti-tank mines, though not designed to target individuals, become instruments of prolonged humanitarian suffering and environmental contamination.